How Egyptian Hieroglyphs Were Deciphered

Perhaps each of us would like to become a brave archeologist for a couple of hours, who managed to decipher the mystery of an ancient civilization. Our article will help you feel like a discoverer for a while.

We at 5-Minute Crafts want to tell you how the Egyptian writings were eventually deciphered.

What Egyptian hieroglyphs are all about.

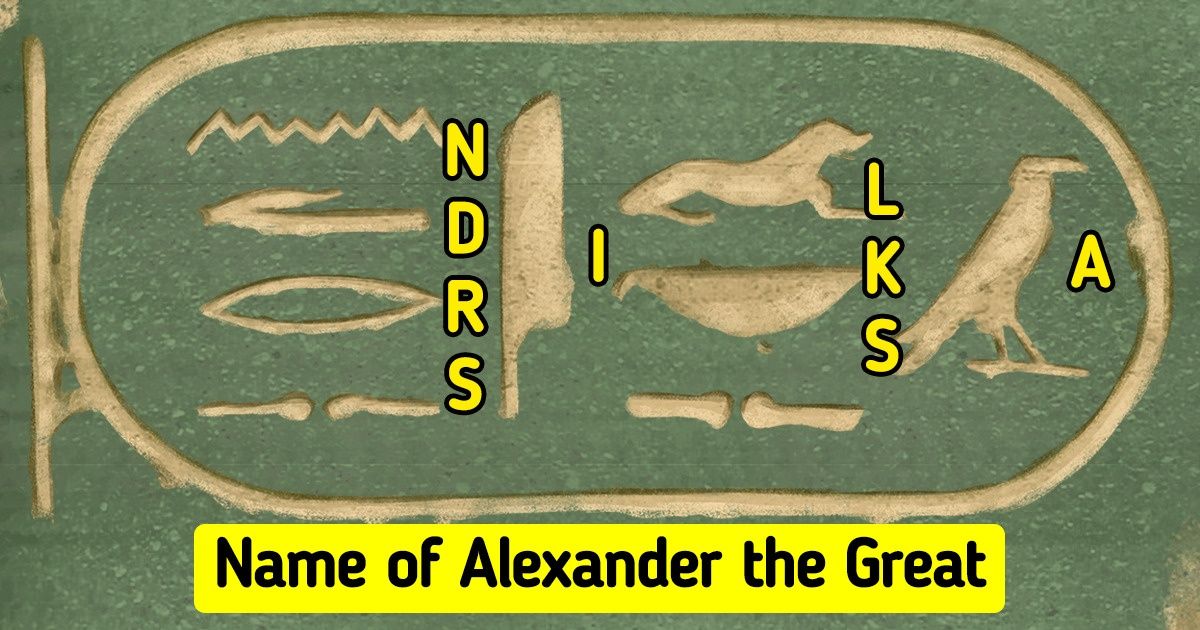

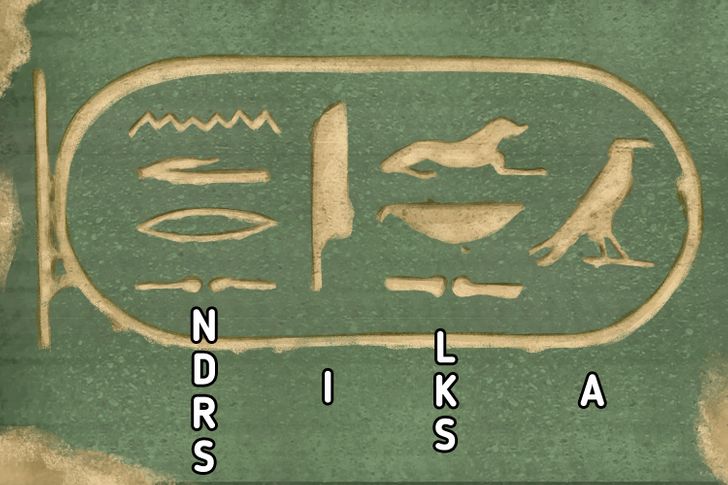

Name of Alexander the Great in hieroglyphs, c. 332 B.C.

Egyptian hieroglyphs is a writing system in the Egyptian language used in Ancient Egypt. It arose from the proto-literate symbol systems in the Early Bronze Age.

The word “hieroglyphs” in Greek means “sacred carving”. There were also other writings that were developing in Egypt — hieratic and demotic — that can be considered a variety of hieroglyphic writing.

Hieroglyphs were used in the Roman period up to 4 A.D. However, when pagan temples were closed in the 5th century, this writing was lost. Despite numerous attempts, no one could decipher them until the 1820s when Jean-François Champollion came close to solving the Rosetta Stone.

There were various types of hieroglyphs, such as cursive ones for example, which were used in religious literature and were applied to papyrus or wood.

Egyptian hieroglyphic writing is the progenitor of most of our modern scripts, such as Latin, Cyrillic, and Arabic.

The Rosetta Stone is the holy grail for Egyptologists.

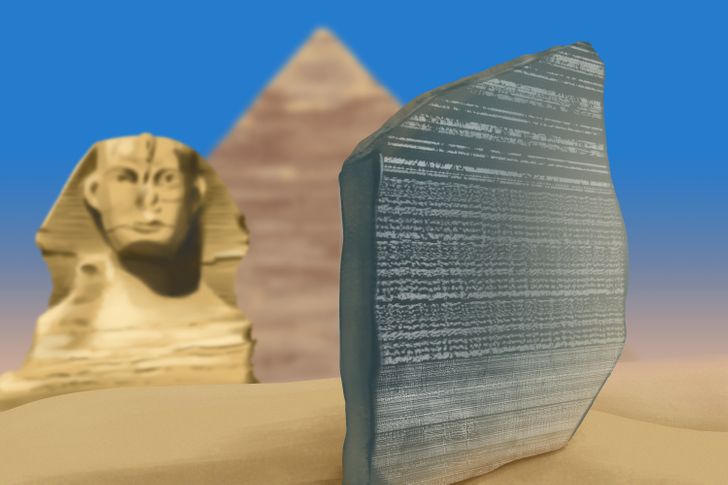

In 1799, a large gray stone with three texts identical in meaning (one in Greek and two in ancient Egyptian languages), carved in hieroglyphs and demotic writing, was found not far from the Egyptian city of Rosetta.

It was named the Rosetta Stone. When the Greek language was translated, it was discovered that the Rosetta Stone contained the decree of the Egyptian priests published in 196 B.C.

In 1801, the stone ended up in the British Museum in England, where Egyptologists studied it, but they failed to compare the languages and understand the Egyptian letters completely. Although the Greek language showed what the hieroglyphs meant, it was still impossible to establish the sound of the Egyptian words because no one had spoken the ancient Egyptian language for about 8 centuries. And since scientists didn’t know how to pronounce Egyptian words, they could not determine the phonetics of the hieroglyphs.

In 1822, a French scientist Jean-François Champollion made a great breakthrough, having proven that Egyptian hieroglyphs were used not only for indicating words but were actually split into phonetical components as well.

The stone, which served as the key to unraveling the ancient Egyptian writing, still remains in the British Museum.

How Egyptian hieroglyphs were deciphered.

Before Champollion, the English scientist Thomas Young started to learn cartouche, a set of hieroglyphs surrounded by a loop, in 1814. Young suspected that something important was written with these hieroglyphs — perhaps the name of Pharaoh Ptolemy, who was mentioned in the Greek text. This guess allowed the scientist to compare the phonetics of the corresponding hieroglyphs, since the name of the pharaoh was pronounced approximately the same regardless of the language. The method worked, and the Englishman repeated this strategy with another cartouche. But suddenly Thomas gave up trying to decipher the hieroglyphs, after having published the results of his work in an article for the Encyclopaedia Britannica in 1819.

Then Jean-François Champollion picked up the same idea. He applied it to cartouches and was able to guess the meaning of the rest of the hieroglyphs. His knowledge of the Coptic language helped him greatly. This language can be considered a descendant of the ancient Egyptian language. Coptic ceased to be a living language, but it still existed in the liturgy of the Christian Coptic Church. Jean-François had known it since a teenager. Thanks to his vast knowledge, the Frenchman realized that the ancient scribes used the principle of a rebus, that is, they broke long words into phonetic components, and then used images to represent these components.

- nfr — beautiful

- mdw — tongue

- ḫpr.j — Khepri (name)